taxes & rebellions

Published on January 1, 2026

"In this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes." Benjamin Franklin

Taxes are as old as the world itself. Since the dawn of time, humans have paid them. But something has fundamentally changed in our relationship with taxation.

In the past, tax rebellions were commonplace. The Fronde in the 17th century, peasant revolts against the taille, the French Revolution itself triggered by financial crisis and tax privileges... French history is dotted with popular uprisings against fiscal oppression.

But today? Nothing. Radio silence. Yet we have never paid as much in taxes in our entire history. So what happened? How did we go from the guillotine for tax collectors to resigned acceptance of record tax pressure?

The answer lies in two words: fiscal invisibility .

The "All-Inclusive" Illusion

The French state has accomplished an extraordinary magic trick: it has made its levies invisible. Gone are the days when a king's representative would knock on your door to collect taxes. If it was too high, people revolted. It was direct, visible, painful.

No need to go back so far in history. Just a few years ago, before the introduction of payroll deduction, we declared our taxes in May and had to make a substantial transfer at the end of the year. It stung hard. Today, everything silently disappears from our payslips.

It's the same logic for VAT. It's included in the displayed price. When you leave H&M with 100 euros worth of clothes, you don't know that you just made a 16-euro transfer to the Treasury. You think H&M is pocketing it all, when they'll only receive 84 euros of the 100 you spent (and will pay many other taxes on top of that).

What If We Had to Pay Everything Ourselves?

A criticism often heard from French people visiting the United States concerns price displays: you never know how much you're really going to pay. A product displayed at $50 will end up costing $55 at the register. It's indeed annoying. As French people, we always forget that you have to add about 10% depending on the state (some more, others nothing like Delaware or Montana).

But I find this transparency healthy. It reminds us that with every transaction, the state takes its share. It reminds us how much the state gorges itself at our expense.

If people tolerate and no longer rebel, it's precisely because of this invisibility.

The Revealing Saturday Shopping Trip

Imagine doing your weekly shopping on a Saturday. You arrive at the checkout, take out your bank card, and the cashier announces: "Attention sir, you need to pay 30 euros more, it's for the state."

No one would remain indifferent to such an announcement.

You go out to the parking lot, load your groceries and take the opportunity to fill up your tank. At the counter: only 25 euros, cheap! You validate, insert your card, then the machine displays: "In addition to the 25 euros, you must pay 35 euros extra: it's for the state."

Angry, you leave with a full tank but an empty wallet. On the way back, you stop at the bakery for a baguette. At least that's not expensive! But the merchant asks you to add 6 cents to the price: "It's for the state."

The Christmas iPhone That Hurts

Later in the week, you decide to treat yourself for Christmas by changing your old 5-year-old iPhone. You go to Apple's website, select the latest iPhone Pro, delighted with your future purchase. When you're about to validate your cart, surprise: Apple asks you to add 222 euros "for the state."

But why? Did the state help develop the iPhone? Manufacture it? Did it participate in developing the new generation processor? Did it finance research and development? No, none of that. Yet it demands its tithe of 222 euros on your purchase.

I've said this for years. If the average worker had to write a check at the end of the year for what they owed, rather than it being taken from their checks before they even see it - there'd be riots in the streets.

— rocketcritter (@rocketcritter) December 3, 2024

The Net Salary Illusion

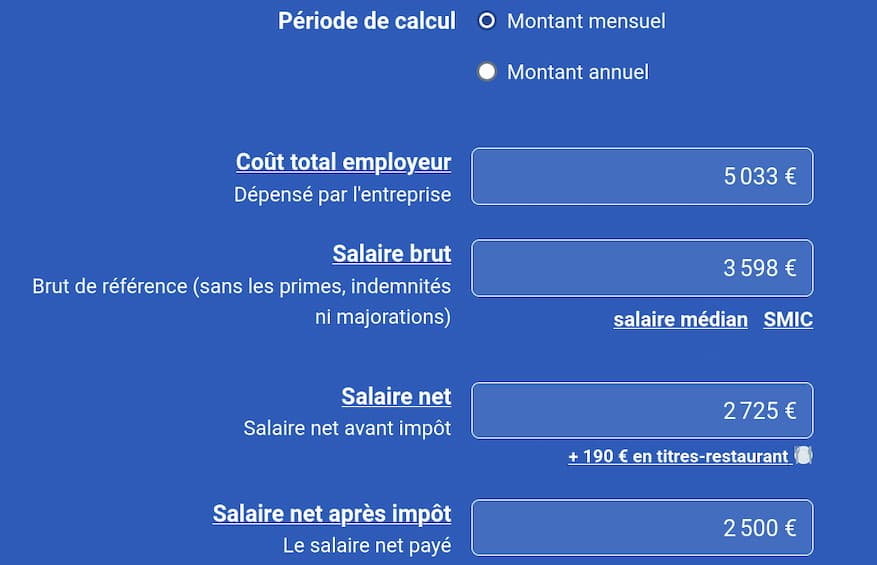

Let's take a concrete example. You're an executive with a net salary of 2,500 euros per month. Instead of receiving these 2,500 euros from your employer, imagine receiving a transfer of 5,033 euros. That's your real cost to the company. That's what it spends for you to provide your work.

On the 1st of the month, while making the transfer for your rent, you receive a notification on your smartphone: "1st of the month, remember to make your transfer to URSSAF, you owe the state 2,533 euros!" More than half your salary goes immediately, about triple what you pay for housing.

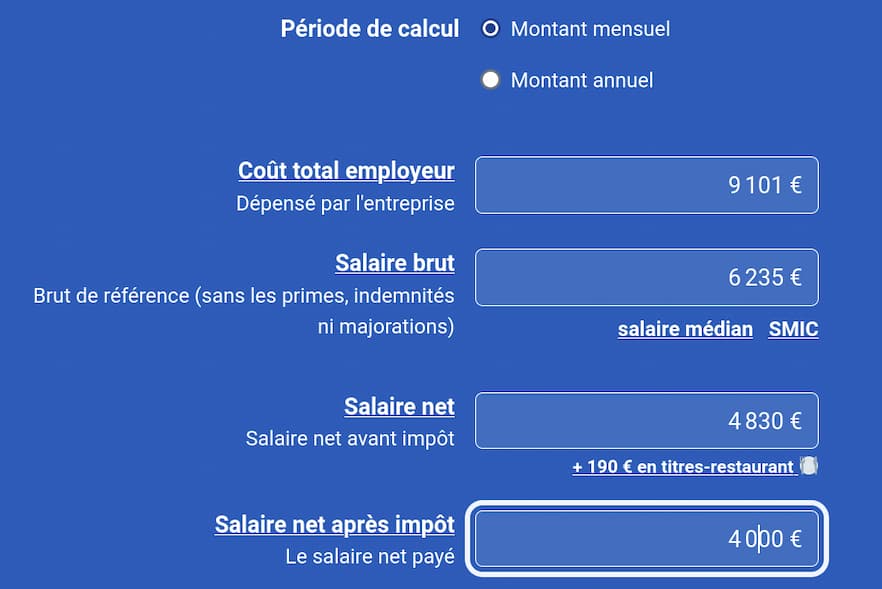

Let's make the exercise more challenging with a salary of 4,000 euros net per month. A good salary for a French person, but nothing excessive. It's not with 4,000 euros that you live in opulence with a villa and Ferrari. It's even rather a mid-career salary, at the age when you have a family to support.

Your employer actually spends 9,101 euros for your work. On the 1st of the month, while paying back your "French Dream" house, you receive an email asking you to pay 5,101 euros to the state. Under the payment, they explain that it's to finance hospitals, schools and daycare centers.

The Disillusionment with Public Services

Two weeks later, you're looking for a daycare spot for your newborn: all are full. There's one left at 400 euros per month. You don't understand: you just paid 5,101 euros to the state, isn't that enough? Do you still have to pay?

A few days later, you get sick. On Doctolib, no appointments available for five days. How do you get a prescription and sick leave quickly?

The Reality of Numbers

The truth is that we pay taxes every day, invisibly. As soon as you have a salary above 2,500 euros net, you give about 70% of what you bring to your company to the state. All of this almost invisibly.

At what point did it become normal to contribute so much? Do you think French people would act the same way if each levy had to be made by themselves?

Collective Blindness

The fundamental problem is that everything has become invisible. We no longer see the extent of our tax contributions. French people regularly demonstrate for more aid, more redistribution, but they don't see that this money comes directly from their own bank account.

This fiscal invisibility is not an accident. It's a deliberate and perfectly mastered strategy. The French state has understood that tolerance for taxes is inversely proportional to their visibility. The more hidden it is, the more accepted it is.

Our ancestors rebelled over levies that were derisory compared to ours. They saw the tax, they concretely measured its weight. We have forgotten it. We have gotten used to seeing only what remains for us, not what is taken from us.

And that's perhaps the greatest fiscal tour de force in modern French history: having succeeded in making a historic tax pressure acceptable by simply making it... invisible.